Native student success needs younger engagement, advocate says

The key to Native American student success on a college campus begins in elementary school, says a long-time South Dakota educator.

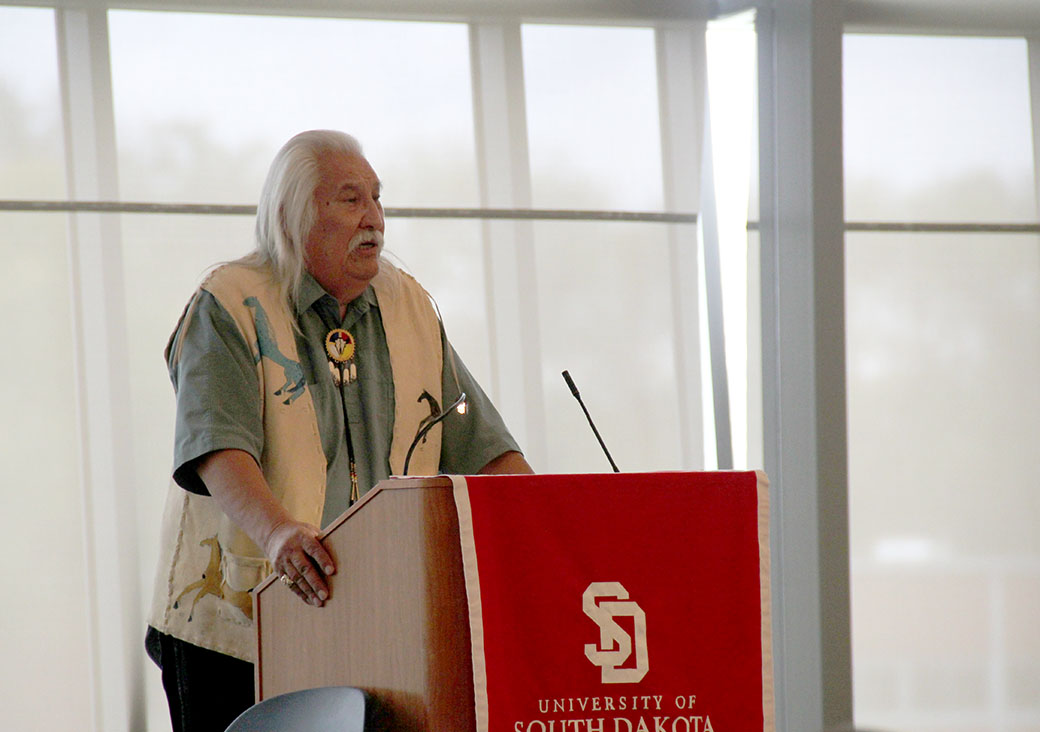

Lionel Bordeaux has been president of Sinte Gleska University, one of the first tribal colleges in the country, since 1973, but he was at the University of South Dakota Monday to talk about challenges faced by Native American students pursuing a degree in higher education.

“We need to come together and sit down and talk about the long range — a vision across the Midwest where tribal and non-tribal people come together for education,” he said.

Bordeaux was born on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation and did not start a formal education until he was 8 years old. He said being raised by his grandparents was a benefit to retaining significant aspects of his culture, an element to his childhood he said is not the case for modern native youth.

“Back when I was child, you were really raised by a village. And everyone was speaking Lakota. It was innate — within you,” Bordeaux said.

For the first three days as a student at Black Hills State University, formerly known as Black Hills State College, in the 1960s, Bordeaux did not unpack his bags. For three days, he waited to go home. It was with his grandmother’s encouragement he went on to graduate.

But the Sinte Gleska president gave numerous examples of the pressures he grew up with that mirror what current Native American students face because of racism, violence, loss of support systems and rampant unemployment on the reservation.

“A lot of our Indian students are walking — between homes, towns. They are idle, wondering what to do next,” Bordeaux said.

There are three tribal colleges in South Dakota, and sophomore Brittany Two Elk attended courses as a high school student at Sinte Gleska. The young woman from the Rosebud reservation said she enrolled at USD after her three older siblings chose not to pursue a degree. She did so in part because she knew it would make her mom happy.

Two Elk was joined by fellow sophomore Anissa Martin, also from Rosebud, at Bordeaux’s speech. Martin and Two Elk said the transition from a reservation to USD’s campus was extreme, but the support system helped ease the transition. The Native American Cultural Center in particular, Martin said, has been a comfort in Vermillion.

“It reminds me of home,” she said.

There is also a Student Tracking and Retention, or STAR, committee that meets weekly to keep track of Native American students’ progress. Kathy Van Kley, coordinator of the “Indians into Medicine” South Dakota office at USD, is part of the committee and said early exposure is one of most significant ways to get more native students on college campuses.

“We need to start in elementary, junior high and high school telling kids about when they go to college, not if,” Van Kley said.

When students are coming from reservations, Van Kley said a lack of resources becomes a major concern. She said students she works with who come from these areas have to worry about basic transportation to campus and if there is gas money available to make the drive — issues not every college student has to address.

USD also participates in the TRIO program, which brings in a number of Native American students to campus to work past a high school level education, Provost Jim Moran said. The next step for the university is to create better alliances with tribal colleges in the state, he said.

“What resonated with me is the whole concept of a journey in some ways. We all come today from all different paths, and yet I think the future that we have has to be together,” Moran said.

(Sinte Gleska University President Lionel Bordeaux says initiatives to get more Native American students to pursue college degrees needs to start as early as elementary school. Bordeaux spoke Monday in the Muenster University Center Ballroom. Megan Card / The Volante)