Ernest Lawrence: USD graduate contributes to the first atomic bomb

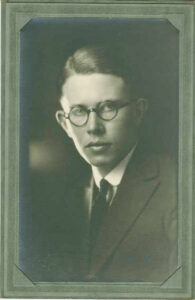

Ernest Lawrence, a USD chemistry student and half the namesake of the Akeley-Lawrence Science Center, had an explosive impact on both the university and the world stage.

Lawrence, a contributor to the construction of the first atomic bomb, was from Canton, S.D. After attending St. Olaf College in Minnesota for one year, he arrived at USD in 1920. He graduated with a chemistry degree in 1922, went on to study at Yale and eventually earning his doctorate at the University of California-Berkeley.

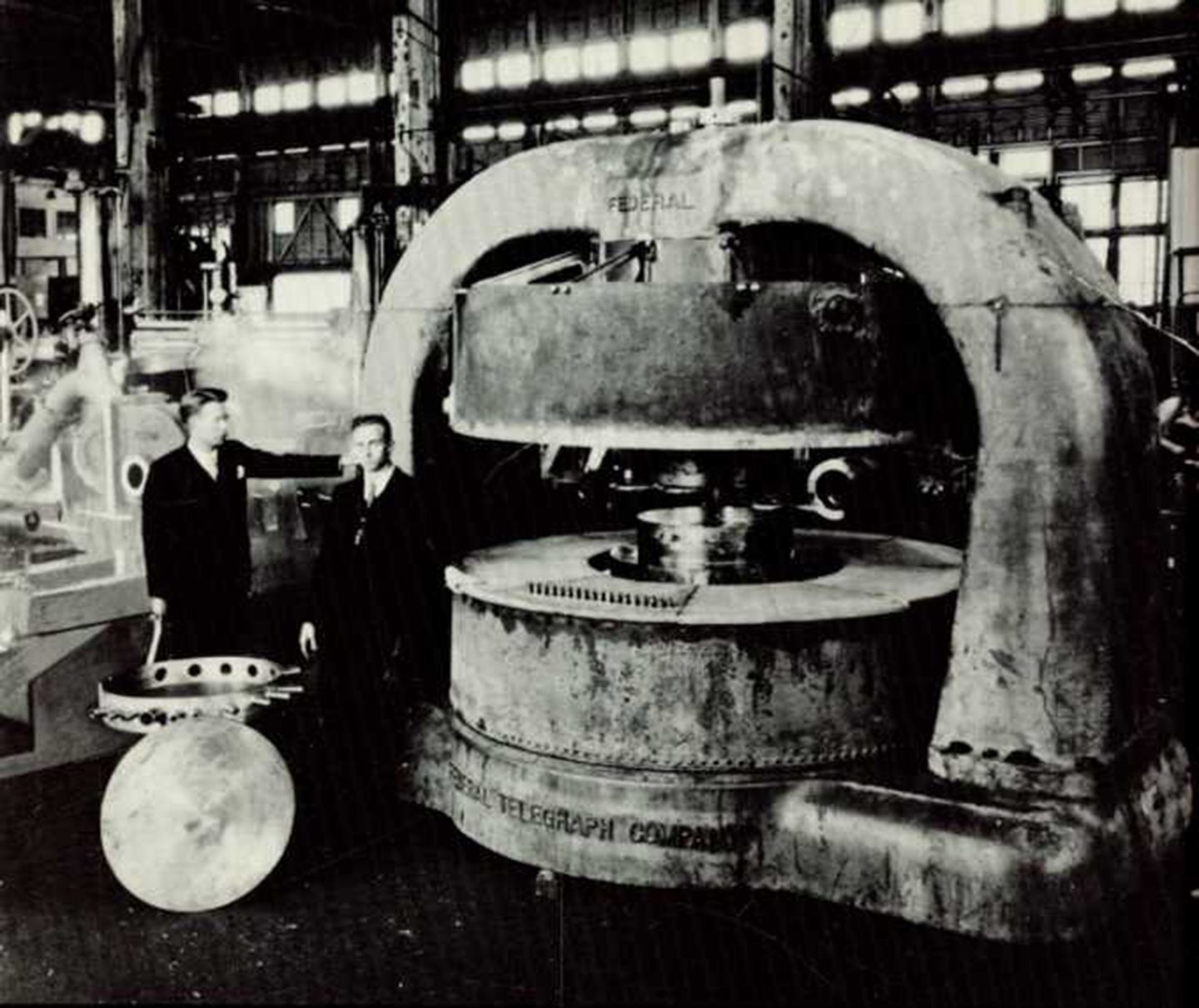

In 1939, while at Berkley, Lawrence invented the cyclotron, an invention used in the Manhattan Project from 1939-1946 to create the first atomic bomb used in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

Christina Keller, retired chair of the USD physics department, said the cyclotron was used in the Manhattan Project to separate uranium isotopes.

“One of the things a cyclotron can do is particles with different masses will go through different size circles,” Keller said. “So when you’re trying to build an atomic bomb, you need uranium, and you need one specific isotope of uranium… what you want to do is isolate or enrich the isotope that’s needed for your explosion to occur.”

While developing the cyclotron, Lawrence was aware he was contributing to the Manhattan Project, Keller said.

“The development of that in the late 20s and early 30s when he was developing- that led up really well into the Manhattan Project,” she said. “Everybody was working on something related to the war effort at that point in time… Lawrence was part of building the atomic bomb.”

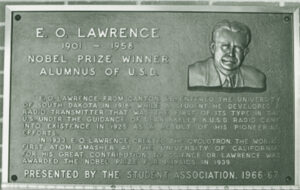

Lawrence received a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his work with uranium and the cyclotron, making him the only USD graduate to receive a Nobel prize.

“Having a Nobel prize winner as a graduate is kind of a big thing for South Dakota, I’m pretty sure we’re the only institute in the state who has graduated a Nobel Prize winner,” Keller said. “But students don’t really know about it, so when I taught the majors physics many years ago, the end of the semester there would be a scavenger hunt for extra credit, and there’d be a ‘which USD graduate won a Nobel prize and what did he win it in and what was it for?’ question and nobody knew.”

During his time as an undergraduate student at USD, Lawrence formed a mentee relationship with Lewis Akeley, a physics professor. Akeley thought highly of Lawrence’s potential as a physicist and student, even proclaiming during a lecture, “Class, this is Ernest Lawrence.” Akeley taught Lawrence by flipping the classroom- Akeley became the student, and Lawrence was the instructor.

“There were a lot of really interesting things happening with physics in the 1920s, quantum mechanics, and it was very new, and Akeley wouldn’t have studied because it was just being developed,” Keller said. “So what Akeley did was he made Lawrence do the lectures. He said ‘you’re going to read the papers, you’re going to put it together and you’re going to lecture to me.’ and he was the only student in that class.”

On the homefront

In his first year at USD, Lawrence approached Akeley with the idea to build a radio wireless set and transmitter.

“(Lawrence) founded KUSD, the first radio station in South Dakota,” Janet Davison, adviser of the USD student radio station, said in an email interview with The Volante. “That station eventually became what’s now South Dakota Public Broadcasting’s flagship station.”

Lawrence created the radio station, South Dakota’s first, because of his interest in science, not journalism, Keller said.

“The reason that he started the campus radio station was that he was interested in electronics, so he’s fiddling around with it; he was more interested in the technology of it than actually reporting the news,” she said.

The building where Lawrence originally began KUSD was named the Lawrence Telecommunications Center in 1982, which was renamed to the Al Neuharth Media Center in 2001.

However, the Akeley-Lawrence Science Center was also renamed that same year, paying homage to the special student and professor partnership Akeley and Lawrence had.

“The naming of the Akeley-Lawrence Science Center was a nice way of remembering the connection between the mentor and the student,” Keller said.

Another legacy the pair left on USD was the Akeley-Lawrence-Norgren scholarship, a Coyote fulfillment scholarship given to 16 science students each year, although Keller said she doubts the recipients of the scholarship understand the history behind it.

Lawrence’s brother, John, who was also a USD graduate, is known as the “Father of Nuclear Medicine.” The pair worked on the acceleration of high energy particles together, using their knowledge to combat their mother’s thyroid cancer.

“One of the things they realized high energy particles can do is they can kill cells. And they can kill both good cells and bad cells, so they can kill cancer cells, which is the foundation of radiation treatment today,” Keller said. “One of their first patients was their mother… they essentially extended her life by 15-20 years. I think that’s really kind of touching, that they had this scientific invention and they trusted it enough to use it on their mother.”

Cedric Cummins, the author of books detailing the history of the university and the history of the College of Arts and Sciences up until 1966 and 1982, both available at the I.D. Weeks library, commended Lawrence as being “one of the institution’s outstanding future alumni” and “among the half dozen researchers who enabled the United States to win the race for the atomic bomb during World War II.”