Underneath the U: The strange history behind USD’s tunnel system

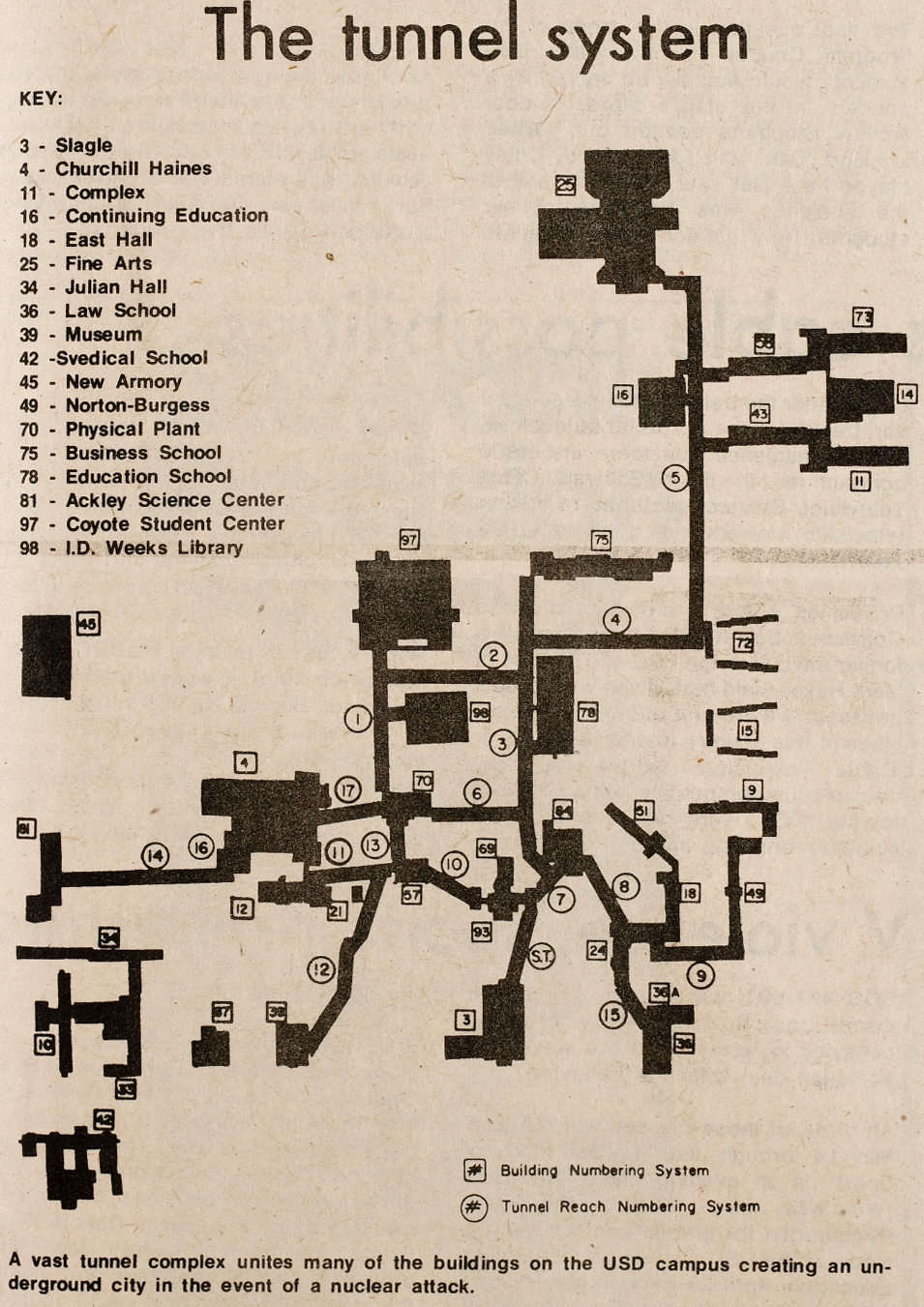

Underneath USD, three miles of tunnels connect power, steam, data and communication lines to buildings across campus. The Facilities Management (FM) crew, who roam the tunnels daily, joke that the labyrinth would make for a good base in the event of a zombie apocalypse.

Actually, they’re not far off. The tunnels are subject to campus lore — a Volante article from the 1980s said multiple students who snuck into the culverts below the Fine Arts building to drink beer often saw a “lady in white” meandering the maze — but during the Cold War, the underground system was prepared to house 15,000 people in case of a Soviet nuclear attack.

Harry E. Brookman, professor of applied science and Brookman Hall’s namesake, designed the first tunnel in 1928 to carry power and steam lines from the old campus power plant to Old Main, a much more pacified purpose than protection from nuclear fallout. As campus expanded and new buildings sprouted through the next few decades, so did the tunnels underneath them.

“When the young people in Vermillion found out about that tunnel, we used to slip through there — only under careful watch,” said Nancy McCahren, a lifelong Vermillion resident, USD student and professor, who said she and her friends snuck into them in elementary school. “You had to be little to get through. We sure as hell had a good time.”

In 1965, the last of the tunnels were built below Cherry Street (then Highway 50) preceding the construction of North Complex.

At the same time, the U.S. and the Soviet Union were two decades deep in a nuclear arms race, stockpiling warheads to counter diplomatic disagreement. Four hundred miles west of Vermillion, 150 minuteman missiles containing nuclear warheads stronger than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in WWII were stationed at Ellsworth Air Force Base outside of Rapid City. In Omaha, 150 miles south of Vermillion, sat the Strategic Air Command (SAC) Headquarters, now Offutt Air Force Base.

“It’s hard to get into the heads of the Soviets to find out their plan of attack,” Col. Robert O’Brien of the North American Air Defense Command said in 1979 when The Volante asked him if South Dakota was a potential target for a nuclear attack.

If the U.S.S.R. targeted major cities, industrial sites and SAC posts, odds were South Dakota would be safe from a direct attack, O’Brien said. But if they planned to bombard missile sites, the “Soviet War plan” would include the state.

In that event, Vermillion, like other cities at the time, had a plan.

With no prior warning, a nuclear strike on Ellsworth AFB could kill 40 percent of the state’s population immediately, according to Cliff Sumption, Chief of Operations for the State Office of Emergency Preparedness in Pierre at the time. With 20 mph eastward winds, fallout particles could reach Vermillion in 24-48 hours.

But with a warning, Clay County, a “host county” because of its location on the edge of two jetstreams, would direct USD’s 6,000 students, the rest of the Vermillion population and residents that couldn’t fit into Sioux City’s shelter underground into the tunnels, which could hold 15,000 people.

Each shelter appointed a “manager” to collect supplies from the “food rationing committees” stationed at local grocery stores and return to the tunnels; students and residents were told to bring the contents of their cupboards with them. Water pipes running through the tunnels, as well as the water tower, would keep residents hydrated.

“You can live two weeks with only water,” Ben Taylor, Clay County Civil Defense Director said in 1979. “You may come out a lot thinner, but you could survive.”

Water, however, could present another problem. If the U.S.S.R. blew out any dams on the Missouri River, from Fort Peck Dam in Montana to Gavins Point Dam in Yankton, Vermillion — 21 feet lower than Yankton — would submerge under floodwaters and townsfolk would be forced to high ground. But that was the worst-case scenario.

The disaster procedure, however, wasn’t well-known to the Vermillion population, McCahren said.

“I don’t think that it was ever published or publicized so the people would know,” McCahren said. “We weren’t sitting around at church or bridge clubs or Carey’s talking about it.”

Luckily, none of the worst-case scenarios have happened, meaning only the FM crew has to fancy the network of six-foot-tall by four-foot-wide tunnels.

They prefer it that way: the entrances are unmarked and motion-activated intrusion alarms are installed near the openings of each one. If someone needs to walk through, they radio the rest of the crew to let them know to ignore the alarm.

Despite a few calls from USD students to convert the tunnels from maintenance mines into underground passageways to shield class-goers from the winter, like at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, Franken said the tunnels are simply too small.

It’s for the safety of the students and everyone else, Craig Franken, director of operations and maintenance, said. If you’re down there, you’re locked between one-way doors and without cell phone service.

The “lady in white” might find you as well.

“We always tell people ‘don’t go down there without a crucifix and some Holy Water in a squirt gun,’” Franken said.