Pandora Papers reveal South Dakota’s role in the global financial system

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has recently begun publishing the Pandora Papers—11.9 million leaked documents showing the offshore accounts of 35 world leaders and more than 100 billionaires, celebrities and business leaders. The publication of these papers drew new attention to South Dakota’s role in the global financial system.

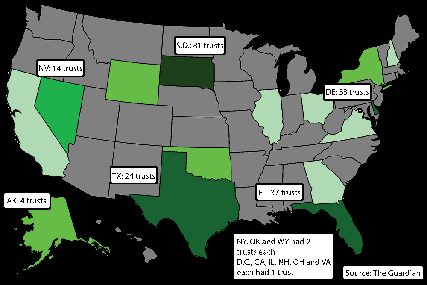

Much of the Pandora Papers are concerned with trusts. Trusts are an arrangement between an asset holder and a trust company where a trustee administers funds on behalf of a beneficiary. The beneficiary may be a third party or, in the state of South Dakota, may even be the asset holder themselves. South Dakota is the state with the greatest number of trusts identified in the Pandora Papers. According to CBS News, of the 201 trusts identified, 81 were based in South Dakota.

South Dakota has made efforts to be an attractive destination for business. The state is one of only seven with no income tax, and one of only two, along with Wyoming, with no corporate income tax.

In 1983, South Dakota became the third state to eliminate the “rule against perpetuities,” a tradition inherited from English common law which places limits on the duration of trusts. According to the Washington Post, in doing so, the state became the first to allow trusts to exist free of state income tax forever.

Tom Simmons, a professor at USD’s School of Law whose work focuses on trusts, estate administration and the estate tax, said that South Dakota’s attractiveness as a destination for trusts isn’t just based on legislation.

“Because the industry is developed here, there’s like 100 trust companies open for business in Sioux Falls alone. In Nevada, by contrast, I don’t know the exact number, but I imagine it’s in the single digits,” Simmons said. “So if you’re looking for a trustee, and you want a professionally trained corporate trustee with oversight and bonding and regulatory oversight… you’d look to a place like either Delaware or South Dakota.”

Simmons said South Dakota also has extensive statutes governing trusts, which come from English common law traditions and were therefore usually governed by case law and judicial decision.

“Basically, you can have too many rules, but generally, the more rules you have, the more there’s an answer to your question, which means you don’t have to litigate it and spend a whole bunch of money having the judge tell you what the answer is,” Simmons said. “So that’s probably number two, is just the comprehensive clarity of our trust laws.”

The state’s lack of an income tax is a secondary attraction, Simmons said, because it only exempts the funds from taxation so long as the trust doesn’t pay out to a beneficiary.

“So that’s not a huge advantage, really, but if you’re comparing states, you’d kind of go, ‘oh well, the state also doesn’t have a state income tax,’” Simmons said. “There’d be that marginal tax savings.”

Timothy Schorn, director of international studies at USD’s political science department, said the revelations in the papers leave the U.S. looking hypocritical.

“We often complain when other countries, such as those in the Caribbean, Central America or even Europe allow for overly secretive banking and hiding of money,” Schorn said in an email interview with The Volante. “The involvement of a number of U.S. states indicates that perhaps our own national laws are not strong enough to address what is happening at the state level.”

Simmons said that trusts are a relatively simple concept in how they are regularly used, and that the secrecy around specific trust accounts is similar to the expected privacy of an individual’s bank account.

“The trust company can’t simply post, oh, Arnold Schwarzenegger has an account here and it has a million dollars in it, because that’s his private financial data,” Simmons said.

Michael Card, an associate professor of political science at USD, said the trust law changes were part of a broader effort by the South Dakota state government to attract banking and financial services companies, like capital solutions company, to incorporate in the state. This included eliminating lending interest limits.

Card said proponents argue that the arrangement benefits the state by creating jobs.

“These are really good jobs. These are jobs for lawyers, these are jobs for accountants, these are just really good jobs,” Card said. “But they weren’t existing in high numbers in South Dakota. And as you know, one of our major exports is educated youth. And so this was a way to keep a number of them in South Dakota.”

Schorn said the benefits to South Dakota are not great, as the state receives only a relatively small flat fee when trusts are set up.

“Theoretically, countries—and American states—who allow this gain a particular economic benefit,” Schorn said. “The money may not actually be in South Dakota… It simply makes South Dakota look like it’s playing a role in money laundering, which it probably is.”

While the number of jobs associated with these trusts is relatively small, Simmons said they still allow people to live in the state and contribute to the local economy.

“Do those people just have to leave our state?” Simmons said. “It’s like, well, we would generally care about people that live here that have jobs, and we wouldn’t just say, ‘well, there’s only a few hundred of you, we don’t care about you.’”

Simmons said the trouble with these trusts comes in cases where the trust may be used to dodge international laws. Notably, Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso funded a trust in South Dakota two months after an Ecuadorian state prohibited politicians from funding trusts in other countries. Simmons said that ideally, trust companies would be able to identify these kinds of laws and avoid these clients.

“The trick with it is, especially if you think about a law that was passed in Spanish, I’m sure, two months ago, potentially not by the federal government of Ecuador but by one of its principalities or states, the idea that every trust company is going to be that up to speed on almost a monthly basis with all the legislative changes over the planet… I’m not sure how you do that,” Simmons said.

Two other individuals named in the Pandora Papers were President Vladimir Putin of Russia and King Abdullah II of Jordan. Schorn said in both instances the countries struggled to excuse the activity.

“It is embarrassing for (Putin) to be called out so publicly. It caused the Kremlin to scramble to come up with a plausible explanation or denial,” Schorn said. “In the case of King Abdullah II, the Jordanian government, at the request of the king, tried to paint the incident as a desire to protect the security of the royal family. But considering how poor Jordan is and how much it relies on foreign assistance, it looks particularly bad to have the King exposed as the owner of numerous mansions around the world.”

Simmons said the state of South Dakota could require trust companies to expand background checks for potential clients to avoid not just clients who have broken laws but those who are potentially seeking to do so. Simmons said it may be difficult to draft legislation defining a credible allegation of potential wrongdoing. The background information can be about the criminal convictions of the client or their other personal details.

“If you think of it in kind of two steps, like one thing, we want the trust companies to do that. And then the second thing is we need to be able to penalize them when they don’t, and for it to be fairly clear for them when they’ve complied with what’s expected, and when they haven’t,” Simmons said. “So they’re not just guessing whether they did enough.”

Any efforts to crack down on these trusts will require international cooperation. Schorn said there has been movement in the European Union, G-7 and G-20 countries to reign these practices in.

“Europe has probably been the most successful, but even then, countries such as Luxembourg, Switzerland and Liechtenstein may run afoul of the wishes of the rest of Western and Central Europe. This is especially problematic for Luxembourg, who is a member of the EU,” Schorn said.

The South Dakota legislature’s ability to crack down on trust companies who may not be doing enough to ensure that the money they handle is legitimate may be hampered by what Card said is called regulatory capture.

“That is when you have a really complex subject that legislators aren’t likely to know about. They know it exists, but they don’t know the intricate details of how it works. And there may not be people in state government who know intricately how it works,” Card said. “The lobbyists who do know how it works can recommend legislation that may not be exactly in the state’s interest.”

The Pandora Papers highlighted how much of South Dakota’s economy is based in the financial sector, which many South Dakotans are not aware of. In a poll conducted by the SDSU Poll, 77% of respondents identified agriculture as the largest sector of the South Dakota economy. Just 2% correctly identified the finance sector.

Card said that public misperception on this issue and lack of knowledge about the ways in which South Dakota legislation has sought to attract the financial sector is tied to a lack of transparency in state government.

“There has to be a right of the public to know some of this,” Card said. “You also need some privacy to get some things done, but at some point, that privacy has to be lifted so that we can find out what happened.”

The breadth and scale of the revelations in the Pandora Papers is largely due to international cooperation. Schorn said the involvement of journalists from so many countries meant the story could be covered extensively and ensured no stone was left unturned.

“The journalists can follow the story to wherever it takes them,” Schorn said. “It becomes much more difficult for leaders and others to hide illegal or embarrassing behavior.”